Hong Kong’s Immigration Department has simplified eligibility and enrollment for the self-service immigration clearance (e-Channel) for qualifying frequent visitors. Visit their website to learn more.

Written by South China Morning Post

A ferry ride across Mirs Bay takes you to Hong Kong’s easternmost island of Tung Ping Chau, which forms the tip of a unique geological formation that is part of the Hong Kong UNESCO Global Geopark. Here, the sea and time have carved and moulded rocks into other-worldly shapes and precise geometric patterns, a temple stands beside buildings devoured by trees, and turquoise waters shelter dozens of coral species. After centuries of habitation, the island’s unique heritage is enticing visitors back to marvel at its many natural wonders.

Refuel

A few village stores in Tai Tong and Sha Tau villages sell soft drinks, bottled water and beer, but they open only at weekends and on public holidays. So, carry enough drinking water and food as the opening of the village stores and their supplies are not guaranteed.

-

A Ma Wan

The A Ma Wan bay will be your first sight of the island’s unique geology as your ferry approaches Tung Ping Chau Public Pier. Unlike the majority of Hong Kong, the rocks here are fine laminated sedimentary rocks, formed from cementation of silt and mud that deposited in a saline lake some 55 million years ago. The sandy beach is strewn with white coral skeletons of more than 60 species of coral found in the coastal waters. In the village of Sha Tau, the Tin Hau ‘Goddess of the Sea’ Temple dates from the mid-18th century.

Tung Ping Chau is part of the Hong Kong UNESCO Global Geopark, and visitors to the island should observe the Geopark safety guidelines to protect the environment and ensure their own safety. While visiting the Geopark, you should not wander off the main sightseeing routes, or hike near dangerous spots such as cliffs, outcrops, slopes or rocky coastlines to prevent accidents. Take note of the warning signs along routes and stay alert to weather changes. Do not damage or deface any objects in the Geopark, remove any rocks, or disturb or harm the wildlife. For more information, please visit the Geopark’s website.

Get me there

Tung Ping Chau is part of the Hong Kong UNESCO Global Geopark, and visitors to the island should observe the Geopark safety guidelines to protect the environment and ensure their own safety. While visiting the Geopark, you should not wander off the main sightseeing routes, or hike near dangerous spots such as cliffs, outcrops, slopes or rocky coastlines to prevent accidents. Take note of the warning signs along routes and stay alert to weather changes. Do not damage or deface any objects in the Geopark, remove any rocks, or disturb or harm the wildlife. For more information, please visit the Geopark’s website.

Get me there

-

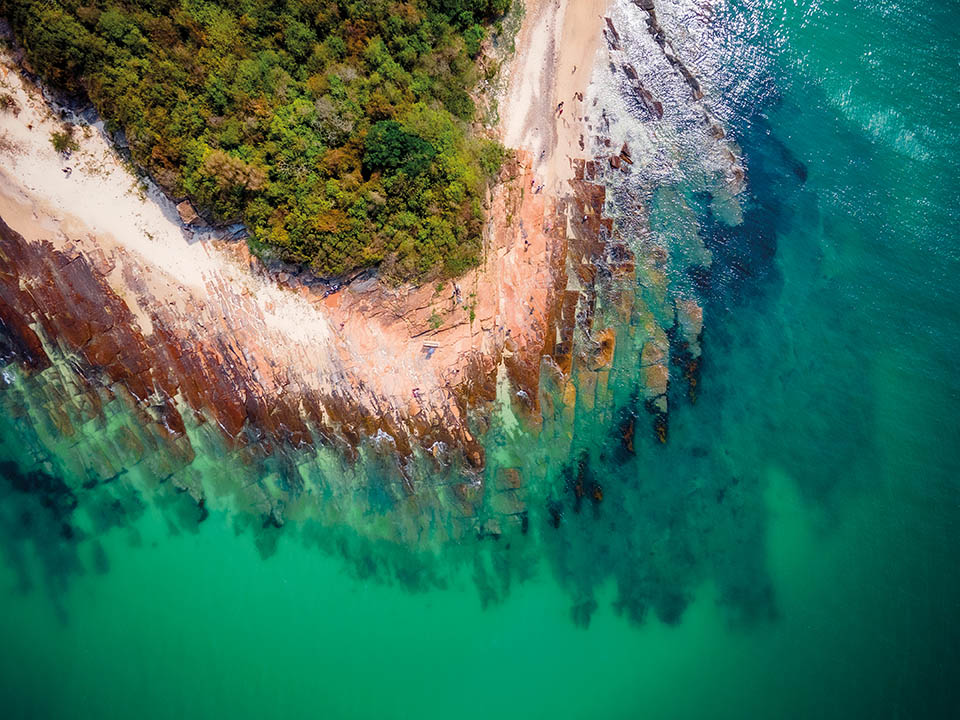

Kang Lau Shek

This headland — the most easterly point of the island that’s regarded as ‘a museum of geomorphology’ — is laid out in tilted, flat rocks, as if the bindings of gigantic books have been buried in the ground. To the touch, the layered texture feels like stacked pages of ancient tomes. Each centimetre of these rocks took a century to form. The Chinese name, Kang Lau Shek, ‘Watchtower Stone’, was inspired by its resemblance to a pair of ancient, two-storey watchtowers. The two rock towers facing the sea offer the best Instagram opportunities, but also remember to photograph the rock pools’ marine life.

Get me there

-

Lung Lok Shui

The Chinese name of these rock formations means ‘dragon descends into the water’. The dragon’s backbone — a zigzag layer of white siliceous rock — strikes out through tilted, flat rock slabs that appear to have been precision cut: some near perfect rectangles and triangles. Face the sea, then turn your head 180 degrees, and the form and colour of rocks changes, as if it’s a giant optical illusion. The straight lines and precise angles of rock pools make them look man-made, and strands of algae, a sprinkle of colourful snails, and darting fish complete the design.

Get me there

-

Cham Keng Chau

A short walk on a well-beaten trail through a shoreline forest leads to Cham Keng Chau — ‘Chopped Neck Island’ in Chinese. Over the centuries, wind and waves widened and deepened a crack in the fractured rock, leaving a small spur cut off by a narrow corridor, which will take you from one sea view to another.

Get me there

-

Cheung Sha Wan

Here the rocks give way to an expanse of white sand on the island’s longest beach. Hefty white chunks of washed-up coral prove how much marine life there is in the turquoise waters next to you. This is the best place for snorkelling or diving.

Get me there

-

Tai Tong Wan

Tai Tong village, on the shore of this bay, seems to have been almost swallowed by the encroaching forest since the departure of people, with the shells of old buildings strangled by banyan tree roots.

Close to the beach, bustling village stores offer a choice of Chinese dishes and seafood specialties: sea urchin fried rice, cockles and sea snails, and — truly delicious — fresh squid fried with chillies.Get me there

Transport

Getting to Tung Ping Chau

From MTR University Station, take bus 272K and get off at the first stop at Ma Liu Shui Public Pier for the ferry to Tung Ping Chau; or you can take a five-minute taxi ride from the station to the pier. Ferries operate only on Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays. The ferry takes about 1.5 hours.

Leaving from Tung Ping Chau

Take the same ferry back to Ma Liu Shui Public Pier and then bus 272K or a taxi back to MTR University Station.

More Routes

Written by South China Morning Post

A ferry ride across Mirs Bay takes you to Hong Kong’s easternmost island of Tung Ping Chau, which forms the tip of a unique geological formation that is part of the Hong Kong UNESCO Global Geopark. Here, the sea and time have carved and moulded rocks into other-worldly shapes and precise geometric patterns, a temple stands beside buildings devoured by trees, and turquoise waters shelter dozens of coral species. After centuries of habitation, the island’s unique heritage is enticing visitors back to marvel at its many natural wonders.

Refuel

A few village stores in Tai Tong and Sha Tau villages sell soft drinks, bottled water and beer, but they open only at weekends and on public holidays. So, carry enough drinking water and food as the opening of the village stores and their supplies are not guaranteed.

Transport

Getting to Tung Ping Chau

From MTR University Station, take bus 272K and get off at the first stop at Ma Liu Shui Public Pier for the ferry to Tung Ping Chau; or you can take a five-minute taxi ride from the station to the pier. Ferries operate only on Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays. The ferry takes about 1.5 hours.

Leaving from Tung Ping Chau

Take the same ferry back to Ma Liu Shui Public Pier and then bus 272K or a taxi back to MTR University Station.